Around the time of the release of Chef Grant Achatz and Nick Kokonas's memoir, Life, On the Line, I read an interview conducted by Grub Street New York where Chef Achatz cited that he "had one of the best meals of [his] life last night." It was at this very spot -- Kajitsu, the famed vegan (yup, you heard me correctly) Japanese restaurant. To further quote Chef Achatz, "What that guy did with vegetables … you don’t even know. Mind-blowing. Mind-blowing." Given the reputation of Chef Achatz in the culinary world, I was quite curious to check it out. Furthermore, a recent article-recipe written by The New York Times Magazine columnist, Mark Bittman, on Chef Nishihara's vegan Worcestershire sauce earlier this year persuaded me to check it out ASAP.

Chef Nishihara worked at Kitcho, one of Kyoto's most regarded kaiseki restaurants, for ten years. During this time, "he gained extensive knowledge of the techniques and traditions of Japanese cuisine," training in kaiseki cuisine as well as the Japanese arts of tea ceremony and flower arrangment. This helped him "develop a deep respect for seasonal qualities of ingredients and the importance of antique Japanese dishware in presentation." Together, these comprise the "integral parts of kaiseki cuisine, in which tranquility, beauty, and hospitality merge to enhance the food."

After Kitcho, Chef Nishihara became the executive chef at Tohma, a soba kaiseki restaurant in Nagano, Japan. Soba kaiseki is a form of multi-course kaiseki cuisine (more on this shortly) that includes hand-made buckwheat soba noodles. Two years later, he came to New York City to head the kitchen at Kajitsu. Here, as he "believes shojin cuisine embodies the spirit and the origin of all Japanese culinary categories while dealing with the constraints of not using foods of animal origin," Chef Nishihara said he "strives to get the very best out of each ingredient, and of using one's creative ingenuity to entertain the customers."

After Kitcho, Chef Nishihara became the executive chef at Tohma, a soba kaiseki restaurant in Nagano, Japan. Soba kaiseki is a form of multi-course kaiseki cuisine (more on this shortly) that includes hand-made buckwheat soba noodles. Two years later, he came to New York City to head the kitchen at Kajitsu. Here, as he "believes shojin cuisine embodies the spirit and the origin of all Japanese culinary categories while dealing with the constraints of not using foods of animal origin," Chef Nishihara said he "strives to get the very best out of each ingredient, and of using one's creative ingenuity to entertain the customers."

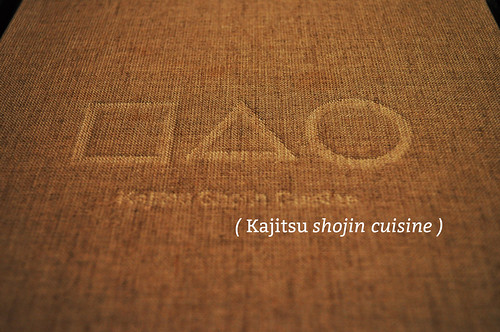

The kitchen at Kajitsu is focused around shojin cuisine, "a type of vegetarian cooking that originates in Zen Buddhism." Though strictly "vegetarian," shojin is "regarded as the foundation of all Japanese cuisine, especially kaiseki, the Japanese version of haute cuisine" which consists of "a multi-course meal in which fresh, seasonal ingredients are prepared in ways that enhance the flavor of each component, with the finished dishes beautifully arranged on plates." Shojin is still prepared in Buddhist temples all throughout Japan today.

Given the "Zen" philosophy embraced in the restaurant's cuisine, it is no surprise that its décor draws influence from minimalist tenets of Zen thinking -- the warmth and organic feeling from the woods and sparse artwork displayed undoubtedly aligns with this belief. The ambiance itself is very, very quiet (you can pretty much hear a pin drop) to the point where it encourages inner rumination. The intentional lighting and the aforementioned backdrop certainly calls a focus on the courses at hand, given that there are very little distractions to take you away from them.

The shapes "○∆□" were taken from a painting sketched by Sengai Osho (1750-1837), a Zen monk, to illustrate one of the most essential principals of Zen: the journey to bring meaning out of something that seems to have none. Kajitsu embraces this and displays this painting as to illustrate its respect for Zen philosophy and the traditions of shojin cuisine.

Dishware and pottery are an integral part of the meal in traditional Japanese cuisine. The repertoire of dinnerware at Kajitsu includes pieces created by master Japanese potters over 200 years ago as well as pieces created by modern ceramic artists. Due to the unique colors and quality of these pieces being unable to be reproduced, dishes are carefully repaired if they are chipped or damaged, resulting in small, noticeable patches. This indicates the "deep respect for the work of old masters and for the shojin tradition of frugality."Instead of going down the sake tasting route (still getting acquainted with the Japanese spirit), I decided to have a pot of the hoji tea (hojicha) -- a dark roasted green tea which the menu claims to pair well with food. Kajitsu sources its highest quality Japanese green teas from Ippodo, a 300-year-old tea maker in Kyoto. I enjoyed the roasted flavor throughout the dinner, and I felt that it definitely went well with the eight courses we had awaiting us ahead. Though I enjoy having the traditional konacha (i.e., coarse, powdered green tea) at sushi restaurants, it was refreshing to have something different than the usual offering. Plus, I loved the handle on this little tea pot -- it was fun to pour!

After contemplating the three tasting menus offered that day -- the four-course Kaze, the eight-course Hana, and the special Takenoko dinner (same as the Hana, with a different fourth and sixth course) -- Christine and I decided opting for the Takenoko tasting would best way to experience Kajitsu menu. I later learned the reason for the dinner being dubbed the Takenoko dinner is because takenoko is the name for the edible part of bamboo (bamboo shoots, essentially) in Japanese, and the differing fourth and sixth courses were focused around takenoko. The offering of this menu began starting March 17, which was earlier that week.

The first course of the Takenoko tasting was the nagaimo hishimochi (hishimochi being red, white, and green lozenge-shaped rice cakes) with spring vegetables and sweet soy gelée. Per our waitress that night, it was to be eaten with a spoon.This course was a well-adorned salad course with freshest raw vegetables I've probably ever had placed throughout the composition of the plate. My palate felt like a novice forager, working its way through a forest of the most exotic greens. The sweet soy gelée layered a touch of umami over the vegetables with its in-between solid-liquid state -- it was a pseudo salad dressing. The nagaimo (a Japanese yam) was an interesting combination of crunchy and soft (like a hybrid of potato and turnip). Subtlety was definitely key. Overall, I found this to be very interesting. It wasn't something I fell in love with, but I appreciated its presentation as well as the deliberate placement on the tasting menu.

The second course was a grated kohlrabi soup with grilled gomadofu with karashi and fresh green pepper corn. Now, I never drink Asian soups (broths, miso soups, etc.) -- I'm more of a Western soup drinker. However, this soup concocted by Chef Nishihara was unbelievable. The soup base was made from grated kohlrabi, which is a type of cabbage whose root comes from the German word for cabbage (kohl) and turnip (rabi, the Swiss-German variant) because the swollen stem resembles the latter. Given the simplicity of kohlrabi, it was hard to believe that it was just that. It had so much overflowing flavor and depth that I slurped every ounce that remained in my bowl until no droplets of soup remained. The gomadofu, typically made from sesame paste, kuzu (a white starch), and water, was warm and had a very thin-skinned exterior -- almost like agedofu (a fried Japanese-style tofu) but softer, more delicate, and unsoggy from the soup. Its texture was firm yet velvety with each bite. The topped karashi (a mustard made from crushed mustard greens) and the fresh green peppercorn (sliced crosswise) gave the soup and gomadofu a spiced kick.

The third course was four-fold: (1) smoked satoimo (taro) with tofu-yo sauce; (2) Brussels sprout with fukinoto paste; (3) spring scallions with white wood ear mushrooms, mustard miso, kaffir lime, and lemongrass; and (4) peach flower nama-fu with shredded daikon. All was served with shredded daikon and a sweet sauce (whose name escapes me now). There was a lot going on here, so I will do my best to convey it all.

{1} The smoked satoimo was served on a fancy dual toothpick. The sauce is made using tofu-yo, which is actually the result of fermenting and aging regular tofu. The sauce was interesting, but because I'm not really a fan of taro, I wasn't too crazy about this dish, mainly because its awkward texture. Christine enjoyed it though!

{2} The Brussels sprout was really good -- the fukinoto paste (made from butterbur buds) created an interesting, subtle variations of bitterness along the palate. Very fresh.

{3} The spring scallions with white wood ear mushrooms, mustard miso, and lemongrass were served in a kaffir lime. This was probably my favorite "item" within the third course. With the presentation both resourceful and aesthetic, it was a very citrus-driven salad of really fresh scallions and white wood ear mushrooms with a light bite from the mustard miso.

{4} The peach flower nama-fu (a kind of wheat gluten) was very gelatinous and had a fruity touch to it. I appreciated its inclusion, but thought it was just okay.

{5} The accompanying shredded daikon was to be dipped in the sweet sauce, which I enjoyed. Crunchy and crisp, the shredded daikon mixed with the sweet sauce gave it a more rounded flavor rather than just texture.

The fourth course was one of the highlighted dishes on the Takenoko tasting -- house-made soba with Kyoto bamboo shoot tempura and accompanying wasabi and scallions. I had never had homemade soba before, and as it is made daily at Kajitsu, it was really fresh. A little firmer than I had originally expected, the house-made soba was served chilled in a light cool broth. The highlight for us, however, was the Kyoto bamboo shoot tempura. It was quite possibly the neatest and cleanest coating of tempura batter I've ever witnessed and tasted. The skin of fried tempura batter was so thin yet remained crunchy all around and intact -- not soggy at all. It was perfect. The bamboo shoots were juicy and crunchy, almost like biting into a piece of fresh fruit, only instead of a sweet interior, it has more of a crisp vegetable consistency. Great course -- its simplicity was what was most astounding, further proof that I'm glad we went with the Takenoko tasting menu.

The next course was the fifth one -- shredded phyllo wrapped yomogi nama-fu with house-made Worcester sauce along with a corn husk packet. The phyllo (i.e., paper-thin sheets of unleavened flour dough) was playfully shredded and wrapped around the yomogi (i.e., Japanese mugwort that yields a muted green color) nama-fu (the white gluten seen earlier). The green interior was very soft and mushy, similar to the consistency of lightly whipped mashed potatoes, with an earthy taste to it. Overall, it tasted (to me, at least) like a tastier fried taro ball in traditional Chinese dim sum.

There were also two accompanying "condiments" -- house-made Worcester sauce (the famed sauce featured in Mr. Bittman's article!) as well as lemon and salt (see photograph below). Christine and I made sure we tried both combinations on each piece. The house-made Worcester sauce was incredible -- similar to katsu sauces I've had before, but so much better! After knowing how much labor goes into making what appears to be a "simple sauce" (40 hours!), you definitely appreciate the sauce's complexities and deliciousness with the shredded phyllo-wrapped yomogi nama-fu. Tangy, a bit sweet, and savory all at once, this sauce will pretty much go well with anything fried. The second combination of lemon and salt (it may have been Himalayan because of its pink color) reminded me, in the best way possible, of the German pancakes at IHOP (probably because of the lemon and the phyllo). It was great to experience the same food, two different ways by means of a condiment.

Along with the yomogi nama-fu were some sides.{1} The grilled cabbage with arugula sprouts and watermelon radish along with snap peas with parsnip purée were really crisp and fresh. {2} The fresh lemon and salt for the yomogi nama-fu shown here, as mentioned previously. {3} The sautéed glass noodles with kinugasa mushrooms and leeks were wrapped inside the corn husk packet. Still warm, as the noodles were smooth and earthy with the vegetables. {4} The roasted chickpeas in shells were just like edamame, only with chickpeas -- loved the roasted, smoky flavor.

By this time of the meal, we were well on our way to becoming totally stuffed.

The sixth course was another Takenoko offering -- {2,4} takenoko gohan, the donabe clay pot cooked rice with grilled Kyoto bamboo shoots and house-made pickles (served family style) along with {1,3} red miso soup with wakame, nameko, and scallions. This was Christine's favorite by far. I liked that the rice was really hot and that the grains closest to the surface of the hot clay pot became a little crusted, giving the rice a more textured character. The Kyoto bamboo shoots were lovely (gotta love that crisp bite with each morsel), too. Even though we both came to our late dinner with practically empty stomachs, we didn't get to finish and enjoy all of the rice -- I was so very disappointed in us for being so full already! The red miso soup (with brown seaweed, Japanese mushrooms, and scallions) was a lot less milder than the traditional miso soups served in Japanese restaurants, so it was very explosive in flavor. It was a good complement to the takenoko gohan. That container was so dainty and cute!

The dessert part of our tasting began at course seven with sakura mochi (glutinous rice) wrapped in salted cherry leaf, which we were instructed by Chef Nishihara to eat from left to right. To the left of the mochi was red bean paste gradually becoming white bean paste with almond flour to the right. Along with the dessert itself, we were given a dish with a wet napkin for cleaning our fingers after eating the mochi with our hands. I thought the interior of the dessert was great -- loved the contrast between red and white bean paste as well as the fresh and moist glutinous rice. As for the salted cherry leaf, I probably could have done without that -- for me, it took away from the mochi -- but nevertheless, I understood its aesthetic and culinary importance.

Our last course (number eight) concluded with warm matcha tea with candies by Kyoto Suetomi from Kyoto. The matcha tea was rich in taste, mainly a pleasant bitterness, with a silky graininess -- funny how oxymoronic words are somehow the best way to describe this gustatory experience. Presented as a blooming cherry blossom, the sakura-shaped candy was very chalky (pretty much like those Valentine's Day conversation heart candies) while the stalk-like leaves were like pâtes de fruits, only flavored with black sesame.

Findings: Overall, our eight-course meal at Kajitsu was very lovely and enlightening. It is hard to put into words the class of flavors in which it is classified (I only can think of an adjective in Chinese that I cannot seem to translate well into English). But if I could attempt to describe it decently, the meal was comprised of clean, refreshing flavors that by no means were bland -- simple yet refined may be the appropriate phrasing.And the biggest mind boggler of this wonderful meal was that it was entirely vegan. The first couple courses eased us into what glorious wonders were to be explored -- they were clearly vegetarian -- but by the third course, you'll pretty much forget that it's all vegetables and animal-free. I mean the presentation alone is enough to distract you from this.

At Kajitsu, Chef Masato Nishihara is certainly an artist in his own right -- the unique pieces of pottery presented serve as canvases on which he paints, however seemingly flawless, breathtaking seasonal landscapes of traditional shojin cuisine. Both from a visual and gustatory standpoint, each course presented for the guest's pleasure envelops and nourishes with intellect and culinary finesse. I learned so much just from writing about our eight-course Takenoko tasting dinner -- I had never heard of nearly 75% of the ingredients prior to this meal. The service was quick and precise, as our waitress was very patient and thorough in her explanations, recited each course eloquently and carefully from practiced, seamless memory.

Those who don toques in the culinary universe are constantly finding ways to challenge themselves to creating new things blazing trails for new ways of cooking. The usual challenges (e.g.,keeping it as locally sourced and seasonal as possible) along with the trending challenges (e.g., embedding new techniques and current technology into what may be referred to as "modernist cuisine") are ubiquitous, though in good way, and are almost to be expected these days. While shojin cuisine has been around since the time of Zen Buddhism, Chef Nishihara set on the task of mastering it, which ultimately means conquering the world of vegetables and vegan ingredients (like Chef David Santos at Um Segredo Supper Club with his recent tasting of vegetables and the famed vegetarian and vegan restaurant, Ubuntu, in Napa). The word substitute is not a part of the gastronomic vocabulary in the kitchen of Kajitsu -- the courses prepared stand proudly lone, without any of its observers and eaters thinking otherwise. Instead, Chef Nishihara is able to craft courses that have ingredients, both familiar and obscure to the Western palate and repertoire, together embodying the tenets and ideas behind shojin cuisine and Zen Buddhism.

I'm curious to see where the restaurant will go once Chef Nishiahara departs at the end of the month -- will it retain the same spirit in cuisine? Will moving to Midtown Manhattan cause any change in ambiance? I guess only time will tell, but for now, it is nice to have pocketed a unique meal like this in my collection of noteworthy eats. It really is captivating what one man, so in tune with shojin cuisine can do without anything of animal origin.

Price point: $100 per person for Takenoko special 8-course tasting menu, $5.50 for each pot of hojicha.

Kajitsu

414 East 9th Street

New York, NY 10009

http://www.kajitsunyc.com

No comments:

Post a Comment